Dieser Text wurde anlässlich der Ausstellung von Nina Torp in der Galerie im Turm in Berlin (27.03.2015 – 07.05.2015) auf Englisch und Deutsch veröffentlicht. Der Katalog wird von Motto vertrieben.

[VOLLTEXT]

Berlin, 31.03.2015

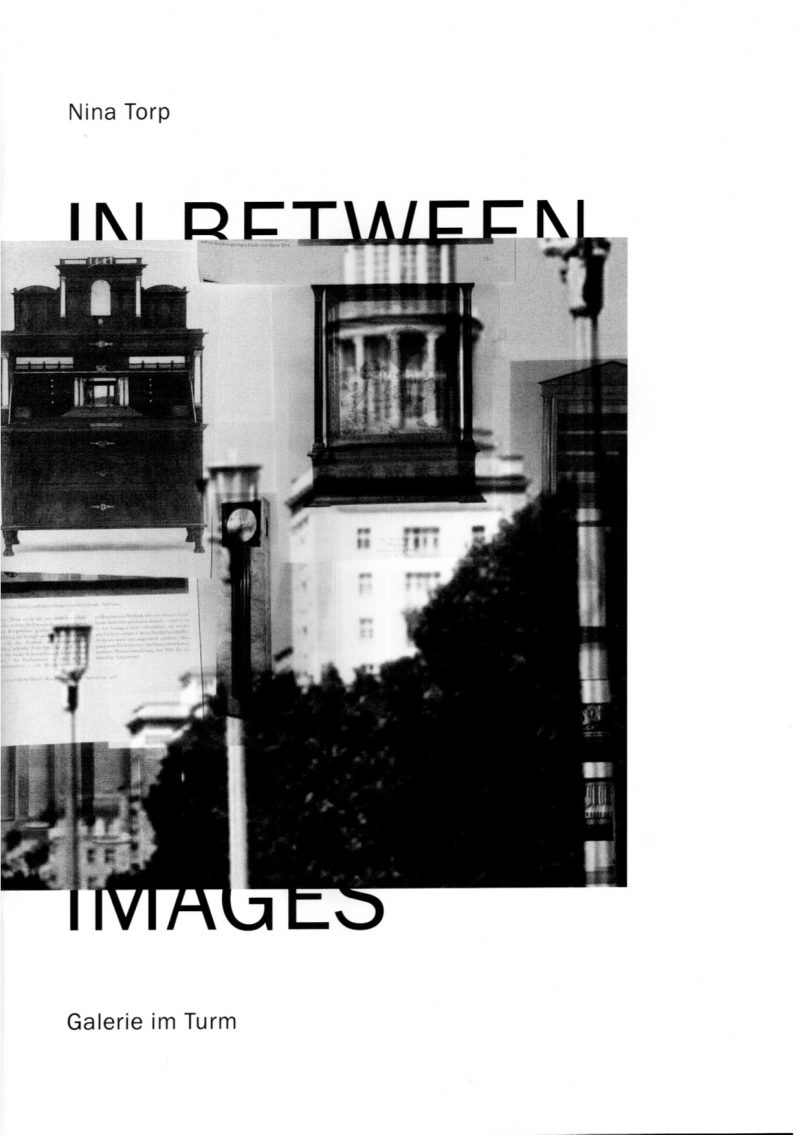

One afternoon, Nina invited me to come and see her exhibition In Between Images at the Galerie im Turm in Berlin. The works presented in the exhibition are primarily interested in history in its contemporary appearance, particularly through a study of the concept of place and the evolution of architectural forms. This exhibition was an opportunity for Nina to develop a ‘site specific’ work around the famous Karl-Marx-Allee. The street is an emblematic place in Berlin, the capital of the GDR at that time, and exemplary for the ‘Socialist Classicism’ in its architecture.

Nina’s piece In Between Images. Karl-Marx-Allee comes as a survey of the evolution of representations of this monumental architecture through time. The present is full of the past. Far from smooth and unified, it is the product of successive layers. The topographic investigation soon meets archaeology in the sense that it gathers together space into the unity of a place by means of a study of stratifications. Layer by layer, analog or digital, the overlay of images does not work, however, on a chronological mode but rather on a mimetic one. It is by the similarity, the continuance of a column, a frieze, the citation or repetition of an ornament on a façade or on some furniture – the concordance of proportions – that a sense of continuity appears.

The three other pieces in the exhibition are gathered under the same title: For we are where we are not. They enrich and nourish the survey Nina carried out in situ, and all have a direct link with the history of Classicism: the first is a film installation dedicated to the Teatro Olimpico, a famous Renaissance theatre built by Andrea Palladio in Vicenza between 1580 and 1585; one is a collection of photographs of Pompeii; and the other is a collection of pictures of neoclassical houses in Norway and Germany found on the Net. The presentation of works connected to places other than Karl-Marx-Allee in the same space highlights Nina’s working method in its exploration of historical time which is not diachronic but synchronic: that is to say, whose ‘thickness’ we seize not directly by means of a work about time divided into past, present and future, but by means of a study of the space in its actual dimension. It is work that focuses in particular on the forms that organize space in a concrete and radical way: architecture.

After our tour of the exhibition ended, we came out of the gallery and headed to the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, which literally means the ‘tower building on the weaver’s meadow’. The Weberwiese is not located directly on Karl-Marx-Allee, but outside of the big avenue, somewhere between Strausberger Platz and Frankfurter Tor.

Already in the exhibition, I noticed a link that seemed very interesting between architecture and theatre, particularly about the installation Teatro Olimpico. This work consisted of a filmed study of the space behind the scenes of the famous theatre of Palladio. The stage of this theatre is based on an illusion whereby the audience sees the stage as a city street in Thebes. Nina filmed in a sequenced shot – camera on her shoulder, her movements in the backstage. In this way, she chose to approach the place by the experience of her body moving in the space, installing it in the present.

I asked Nina if Berthold Brecht and his concept of distancing effect (Verfremdungseffekt) played a role in her investigations into the Karl-Marx-Allee. This prestigious avenue was built not only for the purpose of apartments for the workers but also for the purpose of a political scenography. It is a place of representation, and this is where, once a year, military parades of the socialist East-German regime were held. Faithful in that sense to the Socialist Realism, this architecture intends to break with formalist, capitalist and decadent aesthetics, that is to say, modernism, and so pick up the thread of the story of Classicism and Neo-classicism in the style of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841). Schinkel was instrumental in shaping the appearance of the city of Berlin before the Bauhaus and the Avant-garde.

Socialist Realism, in its application, does not work as an ‘artistic method’ requiring the application of normative rules, but a theory of ‘reality’ governing any artistic creation. It embodies a speculative and likely knowledge of reality, of whose representation the artist should give an ideal form. The task of the artist is to provide a synthesis of reality, which would not be visible to the untrained eye. I think of Brecht, not because of the Socialist Realism, who never applied this theory to the theatre, but because of the modernist appearance of Nina’s hanging: very simple, consisting in clear structures, without any ornament; showing everything and hiding nothing; inviting the viewer to take the measure of the historical depth contained in the facades that adorn the Karl-Marx-Allee, for instance.

The display offers not illusion, but presentation; not emotion, but analysis by a distancing effect of the studied object. Nina’s hanging aims to provide the visitor with the tools of visual analysis, to embody the tension with the architecture that is the subject of this investigation. Everything is connected, in fact, to the history of interpretation and reinterpretation of Classicism. Classical architecture is closely linked to the history of painting and stage design because of their shared practice of illusion and perspective. Thus, Karl-Marx-Allee is designed and built in the style of a painting. In this sense it is exemplary of the public space understood as theatre: it is difficult not to see the avenue as a stage on which episodes of a mythical history were presented; a faithful servant of the ideological struggles during the Cold War.

Speaking of Brecht, Nina remembered that a quote from the author was placed just above the entrance to the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese. We decided to examine this building, and more generally the Berlin cityscape around the gallery. Our discussions reverberated with the architecture we talked about in a very concrete way. The walk was an extension of our discussion in the space of the gallery and it seemed very appropriated to continue to discuss the Karl-Marx-Allee while browsing around. We were not as two walkers inclined to daydream, mixing science and poetry to suit sophisticated discussions among connoisseurs in a beautiful landscape painting from the 18th century. Nor were we like two flâneurs exploring the infinity of modern life and capitalist consumption in the 19th-century Paris, because we were in the middle of a socialist scenography, still intact today.

Nevertheless, we were not far away from the method of exploration Walter Benjamin experienced in his magnum opus Passagen-Werk [Arcades Project] (published posthumous) which he applied to the 19th century; that is to say the century of Marx and photography. If, behind the surface of the décor, there is nothing to find, then the surface itself hides within its own depth. A historical ‘thickness’ can be accessed through a reading of the facades. The skin and clothes of the buildings tell us a story – individual and personal stories whisper of history.

The Hochhaus an der Weberwiese is emblematic of this complex history, made by comings and goings, turning the progress into a spiral. Before the construction of Karl-Marx-Allee – called Stalin Allee until 1961 – the GDR Government planned the new Hochhaus. Started in 1951, under the direction of Hermann Henselmann, the Hochhaus project was designed to defend an objective view of architecture whose ambition was to inaugurate the first ‘sozialistisches Haus’ in Berlin. In the tradition of functionalism from the Bauhaus school, it claimed a modern style. This initial project was halted by the reaction from the Soviet authorities who imposed on East Germany a return to traditional architectural forms, both typical and regional. Henselmann and his colleagues had to review their project and add classical style elements with reference to Schinkel.

During its construction, and since its opening, the building fulfilled a propaganda function as a prototype for the architecture of the Karl-Marx-Allee. It was presented as a model of urban planning at the cutting edge of technology: elevators, central heating, telephone equipment characterized the freshly-built flats. Until about 1948, the urban re-development project in East Berlin under the direction of Hans Scharoun was designed on modernist plans. However, the government quickly condemned these experiments and promoted the Soviet style in it’s place, so Henselmann and former modernists like Richard Paulick were forced to draw the rest of the Stalin Allee in a socialist classical style.

Brecht, initially excited by the project Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, wrote on this occasion the words that were supposed to be placed on the building: “Dieses Haus wurde errichtet zum Behagen der Bewohner and Wohlgefallen der Passenten”. In the end, this sentence was not engraved on the building – instead other words from the poet were chosen to be placed above the entrance: “Friede in unserem Lande, Friede in unserer Stadt, dass sie den gut behause, der sie erbauet hat”.

Our exit from the gallery and our walk towards the Weberwiese were a way to allegorize our eyes by reading traces: facades, surfaces telling us something of what we are today: bodies walking among decorations; reminding us here and there of the history and utopia which both nourishes and bruises. Finally, walking and reading facades made us like Benjamin’s ‘allegoricians’, trying, perhaps, to assemble our perceptions and pictures in a wallpaper where the repetition of historical forms tends towards ornamentation.

Clara Pacquet